OPINION: Time to buy smarter — here’s how

Given the country’s budget outlook, the Defense Department now has no choice but to improve its acquisition performance. But how to do get it done?

We recently addressed that question for our firm, A.T. Kearney.

We compared the defense sector’s acquisition track record and decision processes to those of the private sector. The results were illuminating, and they suggest that the defense sector should look to the commercial world for lessons.

Our complete findings can be found in the white paper, “The Value of Time Matters,” on the A.T. Kearney web site.

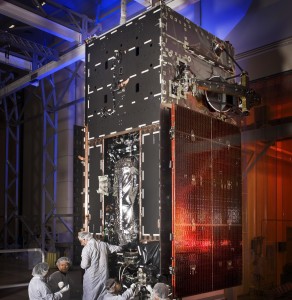

We knew going into our study that the commercial world is widely assumed to do a better job of buying big ticket items like aircraft and satellites. We wanted to see how much better.

We examined the acquisition cycle times for seven of the Defense Department’s top aircraft programs and five of its satellite programs. Acquisition cycle times were defined as the number of months from award of a program contract to declaration of initial operational capability. We then compared the military’s cycle times to commercial fielding times for three kinds of airliners and 11 commercial satellites.

The averages told the story. It took the military nearly twice as long to start operating a new kind of aircraft as it did the commercial sector. The military averaged 114 months, compared to 64 months for new commercial airliners, or a 178 percent difference.

The numbers were even more stark for satellites. The military needed 6.9 years on average to bring satellites into operation, compared to 3.1 years in the commercial world – a 223 percent difference.

It’s true that military aircraft and satellites are typically more sophisticated than their commercial counterparts. But they’re not so much more sophisticated that it should take twice as long to develop and build them. On top of that, defense acquisition planners shouldn’t be underestimating acquisition cycle times by 30 percent, as we found they routinely do for aircraft programs.

Something is amiss. How can it be that the same companies that manufacture airplanes and satellites so efficiently for the private sector are so late for the defense sector?

The root of the problem is this: The commercial world is highly sensitive to the cost implications of time. Congress and the Defense Department are not. Commercial companies know they must minimize technical risks, resist the urge to add new capabilities, and limit reviews to those that are absolutely necessary. There is a tangible opportunity cost of not getting a plane or satellite in service on time, and a penalty in the market for being late.

As a result, the commercial world has a built in incentive to put decision makers in one room and make decisions in a highly-regimented, time-boxed, gated approach. In the defense sector, everyone gets a say: the program executive office; the service acquisition chief; experts in the defense secretary’s office; plus multiple committees on Capitol Hill. This review and approval chain stretches acquisition times, which drives up costs, but in government, there is no marketplace imposing penalties for delays, and nobody in the chain is accountable for the resulting cycle-time induced cost increases.

Officials in the Defense Department and in Congress know this structure is too cumbersome. Changing it would be hard, and so each authority tries to fix troubled programs by digging into them. Reviews are ordered. Budgets are adjusted. Schedules and requirements are changed. The inefficient process that produced the delay in the first place now has the added burden of incorporating changes and writing reports for reviewers.

Our paper describes reasonable changes the Defense Department and Congress should make to reflect the more efficient processes of the commercial world. Our proposals span from incentives to shifts in authority.

We are not saying that every defense Acquisition Category 1 program can be compressed to the commercial sector’s timeline. Military aircraft and satellites may always take longer to build due to their complexity. But twice as long? That’s not an option in this market.

Randy Garber is an A.T. Kearney partner in the Aerospace and Defense and Public Sector Practices.

Arash Ateshkadi is a management consultant with A.T. Kearney. He has a Ph.D. in mechanical and aerospace engineering.