OPINION: Lessons from the leak

It's easy to see how a Congress determined to avoid another 9/11 could give a thumbs up to two far-reaching surveillance programs. No one wants another terror attack, and the programs were so classified that lawmakers couldn't get sanity checks from their staffs, lawyers and old-fashioned pillow talk. Group think prevailed.

Now that the secrets are out, some lawmakers seem flummoxed: What did we think the Patriot Act, the FISA amendments and big data were anyway?

What's hardest to understand is why no one flagged these programs for the sheer implausibility of keeping them secret. The lesson of this saga is that a public debate will come one way or the other when the issue goes to the heart of America's character. These surveillance programs are an element of our national strategy on a par with drone strikes and treatment of detainees. Those secrets were impossible to keep too.

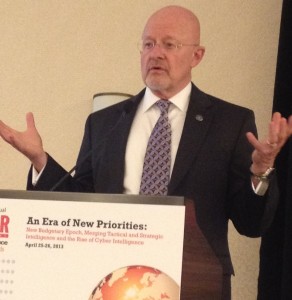

If Congress or the Obama administration had taken the bold step of making the surveillance conversation public, we could have fast forwarded to the debate sparked by a 29-year-old system administrator named Edward Snowden. A public debate would have been ugly, for sure, but that's the hallmark of the democracy we claim to cherish. Fewer operational details probably would have been released, and the media "misimpressions" cited by Director of National Intelligence James R. Clapper could have been avoided or at least debated upfront.

Clapper has said adversaries will change their behaviors now that these secrets are out, but it's hard to see what exactly they're likely to do differently. Stop using the Internet and telephone? It would be hard to plan attacks without them, which might be a good effect. For some reason, the logic of secrecy doesn't extend to Afghanistan, where the allies acknowledge flying signals intelligence antennas on MC-12 turboprops and drones and depicting the locations of the emitters on digital maps. It makes no sense that Afghans civilians can know the extent of surveillance in their country but Americans can't.

Here's the reality: Agencies can ban thumb drives. They can use high-tech document tracking and network security software. They can give contractors and employees polygraphs. In the end, a wise information assurance strategy must take into account whether a topic or policy should be kept secret in the first place.

But here we are. Snowden's last known location was Hong Kong, where he came across as smart and reasonable in a Guardian video interview, aside from a couple zingers about the “architecture of oppression” and “turn-key tyranny” he thinks we're headed for if we don't listen to him.

We're about to find out whether the U.S. government will treat Snowden as a whistleblower, a criminal or something in between. A "Pardon Edward Snowden" petition showed up on the White House web site on the same day he went public.

Top U.S. officials are wrestling with the contradiction of leaks that can't be tolerated, and a national conversation they must accept.

A few days before Snowden took responsibility, President Obama took a question about the surveillance leaks during an appearance in California, saying, “I welcome this debate and I think it’s healthy for our democracy.” On CBS’s Face the Nation, the Republican chairman of the House Homeland Security Committee, Rep. Michael McCaul of Texas, said the leaks will “give us a chance to provide some additional oversight of what the administration is doing," and then he called them a “serious breach.”

Clapper has been the consistent one. He's condemned the media reports and leaks as “reprehensible” and “reckless," and said NSA has requested a criminal probe.

The administration is going to have to decide whether Snowden should be thanked for starting a necessary debate or tarred as an alleged criminal.