Iris ID tech is ready, but agencies might not be

Someday, U.S. federal workers could be free to work their fingers to the bone and forget their six-digit personal identification numbers without risk of losing access to sensitive facilities, documents and computer networks. The National Institute of Standards and Technology has figured out how to squeeze iris images, rather than just fingerprints, onto the personal identity verification cards carried by workers. NIST also has come up with a way to verify fingerprint identities without requiring workers to submit their PINs.

The drawback to fingerprint authentication is that it can be a hassle for workers in rugged, desert regions. “They might have dry fingers or cracked fingers or damaged fingers from doing something like manual labor,” said NIST’s Patrick Grother, the agency’s biometrics and standards testing lead.

Don't put away your yard gloves or forget your PINs just yet. It's unclear whether or how fast the new technology will be put in place. NIST has described how the improvements can be made, but it's up to individual agencies to decide whether to adopt them. One security expert who asked not be named shook his head over the updated PIV card specifications.

“People (in federal agencies) don’t know how to use the technology they have today, let alone add new stuff,” this expert said. In theory, fingerprint readers on keyboards can verify someone's right to access a sensitive document, but in reality there are hundreds or even thousands of offices that are not yet using the PIV cards and fingerprint sensors, the expert said. “That’s the real issue.”

NIST’s role is to push technology forward and that’s what it’s doing. The iris specification and PIN-less fingerprint process are spelled out in a document called “Biometric Data Specifications for Personal Identify Verification (Special Publication 800-76.2),” released on July 12.

Intelligence agencies are exempt from the 2004 presidential directive that led to the PIV cards, but the security expert said those agencies are using similar technology. Fingerprints and iris scans are used to control access to some rooms, but not to control access to networks. PIV cards are used in the Department of Homeland Security and the Defense Department, where they are called CAC cards, short for common access cards.

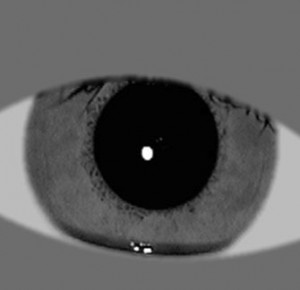

Smart PIV chips on the cards are loaded with fingerprint templates, which are the unique patterns of points called minutiae where fingerprint ridges end or divide. Given the drawbacks of fingerprints, NIST got to work figuring out how to put iris scans onto the cards in addition to print templates. Unlike fingerprints, the irises would be stored as complete gray-scale digital images. The user would present his or eyes to any of a variety of infrared iris sensors developed in the private sector, and a computer would decide if there’s a match. The iris sensors work fine through standard eye wear and contacts. The only limitation would be specialty contacts, like those with “the name of your favorite football team around the iris,” Grother said.

Then there’s the issue of the personal identification numbers. Authenticating someone’s identity with today’s cards requires downloading fingerprint templates and comparing them to live prints from the cardholder. Having millions of cards out there with downloadable fingerprints made security officials nervous, and so an extra security step was put in place. A cardholder must enter his PIN before the template goes anywhere. If someone finds or steals a card, the data can’t be downloaded from it without the PIN.

NIST's new biometrics document also suggests a way to do away with that PIN step. It tells card issuers how to install fingerprint recognition algorithms onto the cards so that the fingerprint comparison can be conducted on the card. Because the template never leaves the card, there is no need to type in a PIN, Grother said.

“The trouble with PINS, of course, is that we forget our PINS – some of us do,” he said.