Features

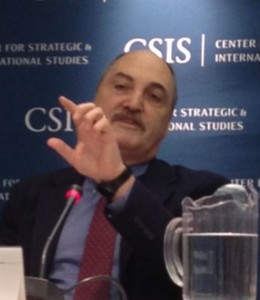

McAfee exec on Mandiant, cyberspies and costs

The Internet security firm McAfee takes a traditional view on the question of whether private companies should name names when it comes to responsibility for cyber attacks and espionage. Its answer is no. McAfee describes events in dry, geographic terms, without references to governments. It's a quaint approach compared to that of Mandiant, the U.S. cyber forensics company that earlier this year accused a Chinese “cyber espionage unit” of stealing American intellectual property and blamed China for hacking the New York Times. In an interview with Deep Dive, McAfee’s Tom Gann explains his company's approach to attribution; its support for a public-private partnership with the U.S. government; and its decision to underwrite a cybercrime and espionage cost study by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington, D.C., think tank.

On the Mandiant Report >>

“When we start thinking about reports of that kind, we really think that those sorts of estimates are best done by governments. To do that kind of work really requires tactical intelligence and also requires human intelligence on the ground, and governments are better suited than companies to drive that kind of research.”

Saying no to attribution >>

“We’re just not in the business of doing country attribution. We’re really in the business of doing technical analysis of attacks and explaining how they occurred and how they can be defended. That’s really our sweet spot. As an organization we felt more comfortable staying in the area of our genuine expertise as compared to trying to pretend we’ve got governmental resources, which we don’t.”

Working with NIST >>

“We signed an MOU with the cybersecurity NIST lab to share our technology, to continue a dialogue with NIST on how the (cybersecurity) framework can be robustly built out. To the degree to which it stays a true public-private partnership, we’re very excited.”

Obama’s cybersecurity executive order >>

“So much of the action is really about implementing the executive order in a way that works for the government, works for the industry.”

Limited legislation >>

“…we’re the most interested in the areas of legislative activity where there’s broad bipartisan agreement, such as FISMA (Federal Information Security Management Act) reform, such as enhanced R&D for cybersecurity, and then over time getting to resolution on information sharing where there’s broad agreement.”

Let the facts lead the way >>

“We underwrote the (CSIS cybercrime, espionage cost) study and partnered with a highly credible think tank that was asked to let the facts go where they go.”

How cybercrime steals jobs >>

“If you look at the companies that lose intellectual property, lose sales, that’s an example… If a company gets hit with significant financial losses and gets shut down, or doesn’t have the funds to expand in a new market, that can produce job loss.”

Measuring the “true” costs >>

“When you add the word true, you’re trying to say, ‘Hey we’ve got some smart economists who tried to apply good methodology here, and not do something that was just kind of a rush job.’”

Other studies inflate damage estimates >>

“Typically in these studies what you do is take a sample of say a hundred companies and you extrapolate those losses….That model of a survey doesn’t do a good job being dynamic. So, one company’s cybersecurity losses and intellectual property may then become the benefit of a competitor of that company domestically, who may get more market share….When you do these valuations and use a very simplistic model you get kind of screwy numbers.”

Electronic jamming specialists to get new tool

The Army's electronic warfare advocates must be crossing their fingers that bid protests won’t delay work under a software contract awarded to Sotera Defense Solutions of Herndon, Va., earlier this month. Two years from now, the new software, called the Electronic Warfare Planning and Management Tool, could completely change the way U.S. soldiers go about jamming enemy transmissions, including those that trigger some kinds of improvised bombs.

Today, electronic warfare officers, or EWOs, must fly on board MC-12 turboprops to plan how to block emissions detected by signals intelligence collectors. With the new planning tool, they’ll be able to do that and 22 total functions from computers on the ground.

The Army wants the technology to be ready for testing by soldiers sometime between July and September 2015. On July 11, the Army announced that the planning tool is now in the engineering and manufacturing development phase.

The new tool is one piece of a broader modernization effort that's facing long budget odds. Another element is a proposed series of jammers called Multifunction Electronic Warfare systems or MFEWs. A backpack version would let foot soldiers knock out an adversary’s comms or jam a specific frequency, such as one used for triggering IEDs.

In a May interview, Col. Jim Ekvall explained how the two systems – the planning tool and MFEW - would work together:

Intelligence analysts “determine that a new frequency is being used to trigger IEDs. That info would be sent to the planning tool. The planning tool would inform the MFEWs elements, you need to attack this frequency.”

For Ekvall, getting modern equipment into the hands of EWOs would be the best way to convince commanders to make full use of their electronic warfare options.

“It’s a little bit hard to sell the importance of your craft, when you’re not able to do so on par with the field artillery guy that’s got a whole system that allows him to do this for the commander,” said Ekvall.

He knows because he's a former artillery man.

Protecting satcom without going broke

The U.S. military faces a satellite communications conundrum. It’s convinced that in a hot war, China and other countries wouldn’t hesitate to throw everything they have at American satellites and the drone video and battle orders they carry. Everything means kinetic anti-satellite weapons like the one China launched at one of its own satellites in 2007; lasers or microwaves; cyber attacks on command and control stations; and old-fashioned jamming.

Here’s the conundrum: The Pentagon knows, or should know, that it’s in no position to stay ahead the way it did in the Cold War – by starting massive R&D programs followed by multibillion dollar industry competitions and weapon procurements.

So what to do?

Enter the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. The Washington, D.C., think tank offers some bold recommendations in a report unveiled in Washington this week by Rep. Doug Lamborn, the Colorado Republican whose district includes Air Force Space Command.

The report, “The Future of Milsatcom,” was written by satellite technologist Todd Harrison, a former Air Force reservist and Booz Allen Hamilton employee.

For starters, Harrison says claiming a military communications satellite is not a weapon would be like saying an M-16 is "merely an enabling capability for the ammunition." With U.S. satellites beaming spy video and battle commands around the world, it's naïve to think space won’t be militarized. “From the perspective of other nations, U.S. military space systems are weapon systems, and space is a domain of warfare that can and will be contested,” he writes.

The best the U.S. can do is steer the space competition in a more favorable direction. He wants the country to rely on frequency hopping and other passive defenses, plus operational workarounds like processing videos on board unmanned planes -- only the nuggets would be sent to analysts via satellite.

Harrison’s other top recommendations:

Don’t go bankrupt arming satellites >>

• “…instead of developing shoot-back capabilities in space, DoD could invest in improving its capability to attack the source of ASAT threats on Earth.”

• Avoid playing into an adversary’s hands: “….the attacker will have an inherent cost advantage because the cost of building more anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons is likely to be significantly less than the cost of deploying additional shoot back or escort satellites.”

Add a middle ground between protected, unprotected comms >>

Today, tactical comms rely on unprotected commercial and government satellites or the same highly-protected satellites the president would use in a nuclear crisis: “A new middle tier of protection could be created to extend a lower level of protection to more tactical users. It would be funded by drawing resources from unprotected SATCOM programs, potentially using hosted protected payloads to expand capacity at a lower cost."

Ask Pacific allies for help >>

More deals could be done like the bandwidth-sharing agreement the U.S. reached with Australia in exchange for paying for a Wideband Global Satcom spacecraft: “As part of its rebalancing to the Asia/Pacific region, the United States could partner with Japan, South Korea, and Australia to host protected Advanced Extremely High Frequency (AEHF) payloads on one or more of their satellites in exchange for limited use of the global AEHF constellation.”

Get the Navy and Army out of the space business >>

The Army runs the satellite operations centers for the Wideband Global Satcom payloads, and the Navy runs the Mobile User Objective System satellite network for the other services and intelligence community. One service could manage it all more efficiently: “The Air Force would be the most likely candidate to assume this responsibility, since it already manages the largest share of the MILSATCOM enterprise.”

Fewer people means fewer bad ideas >>

“...the staffs of existing program offices should be reduced to limit the number of people thinking of ways to change requirements. A staff reduction would also allow the contractors building the systems to reduce their overhead costs since they would not need as many people assigned to interface with program office personnel."

Damage from cybercrime could be overstated

The cybersecurity firm McAfee took a licking in the blogosphere last year for claiming that cybercrime and spying cost the world’s economies $1 trillion dollars a year. A headline on Forbes.com screamed: "McAfee Explains The Dubious Math Behind Its 'Unscientific' $1 Trillion Data Loss Claim."

The trillion dollar figure has been bandied about for years, and not just by the cyber industry. President Obama told a White House audience in 2009 that “last year alone cyber criminals stole intellectual property from businesses worldwide worth up to $1 trillion.”

For whatever reason, criticism of the big number came to a head last August, and so in October McAfee began underwriting a study by cybersecurity experts James Lewis and Stewart Baker of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

The study's initial report, “The Economic Impact of Cybercrime and Cyber Espionage,” doesn't blow the trillion dollar estimate out of the water, but it places it on the far side of the range of possible damages from stolen blueprints, paralyzed networks, and hacked bank accounts.

For the U.S., $70 billion to $120 billion a year would be a good “first guess” about the dollar impact, Lewis told an audience at CSIS headquarters (his report places the low range at $24 billion). The U.S. is one of the world’s major cyber targets, which means that the global tally is “likely measured in hundreds of billions of dollars,” according to the report. An accompanying chart puts the global damage at $300 billion to a trillion dollars.

McAfee said it’s glad a more rigorous estimate is now taking shape: “The numbers are the numbers,” said Tom Gann, McAfee’s vice president for government relations. Past studies settled on “screwy numbers” - some naively low and others unrealistically high -- because they were based on simplistic models or extrapolation, Gann said.

“This is the best study of its kind because it uses very sophisticated econometrics modeling that peer-reviewed economists that CSIS worked with gave the thumbs up to,” Gann said.

No matter what method is used, no one is saying that estimating cyber impacts will ever be easy or precise. Lewis said putting a value on cybercrime and espionage reminded him of studying medieval economies back in graduate school. It’s easy to find anecdotes, but a lot harder to find reliable data.

“This is a fairly normal estimation problem in some fields, either intelligence or in economic history,” he said. “The data is either sparse or distorted.”

He and Baker avoided surveying corporations or other cyber targets, as has been done in other studies. CSIS tried that in a previous study, and Lewis said he was unhappy with the results. The problem with surveys is that not everyone responds. Extrapolating from the numbers given by those who do respond can distort estimates.

He and Baker decided to try a modeling technique in which they identified the key factors -- reputation damage, for example -- that add up to the overall costs of cybercrime and espionage. They found reliable numbers in the economic literature or made estimates from other sources. "This is a standard econometric technique," Lewis said by email.

Lewis said it’s easy to assume grave damage from cybercrime and spying: “If you’re not saying electronic Pearl Harbor, then you’re saying the cost of this is worse than the Black Death." He and Baker went into the study asking, “How do I know it’s actually as bad as we say it is?” They found estimates as low as $6 billion and of course the trillion dollar number. “Generally from an economist’s point of view, you’d prefer a narrower range,” Lewis said.

The CSIS range is still large, and Lewis said it will be refined through further study.

Iris ID tech is ready, but agencies might not be

Someday, U.S. federal workers could be free to work their fingers to the bone and forget their six-digit personal identification numbers without risk of losing access to sensitive facilities, documents and computer networks. The National Institute of Standards and Technology has figured out how to squeeze iris images, rather than just fingerprints, onto the personal identity verification cards carried by workers. NIST also has come up with a way to verify fingerprint identities without requiring workers to submit their PINs.

The drawback to fingerprint authentication is that it can be a hassle for workers in rugged, desert regions. “They might have dry fingers or cracked fingers or damaged fingers from doing something like manual labor,” said NIST’s Patrick Grother, the agency’s biometrics and standards testing lead.

Don't put away your yard gloves or forget your PINs just yet. It's unclear whether or how fast the new technology will be put in place. NIST has described how the improvements can be made, but it's up to individual agencies to decide whether to adopt them. One security expert who asked not be named shook his head over the updated PIV card specifications.

“People (in federal agencies) don’t know how to use the technology they have today, let alone add new stuff,” this expert said. In theory, fingerprint readers on keyboards can verify someone's right to access a sensitive document, but in reality there are hundreds or even thousands of offices that are not yet using the PIV cards and fingerprint sensors, the expert said. “That’s the real issue.”

NIST’s role is to push technology forward and that’s what it’s doing. The iris specification and PIN-less fingerprint process are spelled out in a document called “Biometric Data Specifications for Personal Identify Verification (Special Publication 800-76.2),” released on July 12.

Intelligence agencies are exempt from the 2004 presidential directive that led to the PIV cards, but the security expert said those agencies are using similar technology. Fingerprints and iris scans are used to control access to some rooms, but not to control access to networks. PIV cards are used in the Department of Homeland Security and the Defense Department, where they are called CAC cards, short for common access cards.

Smart PIV chips on the cards are loaded with fingerprint templates, which are the unique patterns of points called minutiae where fingerprint ridges end or divide. Given the drawbacks of fingerprints, NIST got to work figuring out how to put iris scans onto the cards in addition to print templates. Unlike fingerprints, the irises would be stored as complete gray-scale digital images. The user would present his or eyes to any of a variety of infrared iris sensors developed in the private sector, and a computer would decide if there’s a match. The iris sensors work fine through standard eye wear and contacts. The only limitation would be specialty contacts, like those with “the name of your favorite football team around the iris,” Grother said.

Then there’s the issue of the personal identification numbers. Authenticating someone’s identity with today’s cards requires downloading fingerprint templates and comparing them to live prints from the cardholder. Having millions of cards out there with downloadable fingerprints made security officials nervous, and so an extra security step was put in place. A cardholder must enter his PIN before the template goes anywhere. If someone finds or steals a card, the data can’t be downloaded from it without the PIN.

NIST's new biometrics document also suggests a way to do away with that PIN step. It tells card issuers how to install fingerprint recognition algorithms onto the cards so that the fingerprint comparison can be conducted on the card. Because the template never leaves the card, there is no need to type in a PIN, Grother said.

“The trouble with PINS, of course, is that we forget our PINS – some of us do,” he said.

Interactive maps track crime, terror routes

Southern Command and the State Department want countries outside the Southcom area to join the unclassified information sharing network the command created last year. The Whole-of-Society Information Sharing Regional Display website, or WISRD, is one product of the Obama administration’s 2011 initiative to get nations working together to fight trafficking of drugs, counterfeit medicines, people and possibly even weapons of mass destruction.

U.S. officials are increasingly concerned about what they call convergence, the tendency of terrorists and criminal groups to collude along trafficking routes. “These organizations can then move personnel, cash or arms — possibly even a weapon of mass destruction— clandestinely to the United States,” retired Adm. James Stavridis warned in a May 31 commentary in the Washington Post.

WISRD lets decision makers geospatially visualize those routes and share information about them. Participants from the U.S., allied countries and non-governmental organizations can sign onto the secure WISRD Internet site and add icons to Google Earth maps or simply view what others have posted. They can share the locations of go-fast boat interdictions or places where criminals have dumped toxic waste. They can denote neighborhoods with high rates of illiteracy and dissatisfaction with government services, social factors that criminal organizations like to exploit.

The data is stored in a non-government cloud by Amazon. The Arlington, Va.-company Thermopylae Sciences and Technology, provides software, called iSpatial, that lets users place icons on maps and associate them with text and photos.

So far, WISRD has been used mostly among the 27 nations in the Southcom area, which covers Latin America and the Caribbean. The State Department wants members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development to consider using WISRD too. OECD’s 34 members include countries far from Latin America, including most of Europe, Australia and Japan.

The U.S. wants to put more knowledge in the hands of decision makers at all levels, and not just in Latin America, said the DIA’s Norberto “Rob” Santiago, chief of the knowledge management division in Southcom’s intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance directorate.

Expanding WISRD would be “a win-win situation for the OECD as well as for the (U.S.) government in terms of being able to reuse, repurpose this effort,” Santiago said.

The geospatial renderings make it easy to visualize things like trafficking routes, but there is also a political dimension. The visualizations make it hard for decision makers to downplay or overlook the scope of the trafficking problem.

On top of that, WISRD gives allies a recipe for generating information in formats that assure they can be shared. The goal is “having at least some common capability to help partners be able to manage information and display it and share it,” Santiago said.

The State Department has been using the OECD Task Force on Charting Illicit Trade to get the word out about WISRD.

When President Obama announced the Strategy to Combat Transnational Organized Crime in July 2011, Southcom at first tried to complete its info sharing assignment by traditional means: Reports and PowerPoints were produced. “You can imagine that by the time you got to the 20th slide, you were completely lost. You had no idea what the first attribute or element was,” Santiago said.

The decision was made to geospatially render the information and give participants the ability to post information on the maps, as is done in the classified realm. WISRD is different because its content is unclassified and available on a password-protected Internet site.

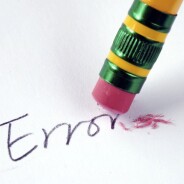

The perils of polishing transcripts

Public trust is a terrible thing to lose, and the intelligence community will have to win trust back one small step at a time. Here's a good place to start. When a top intelligence official talks to reporters, the community should end the practice of cleaning up the official transcript. The actual words spoken today form an important record for journalists and historians who will one day try to understand these times.

As surprising as it is in the wake of the Snowden affair, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence seems perfectly content to have on its website a transcript that it knows is less than accurate.

How did this happen? On May 22, Dawn Meyerriecks, the community’s acquisition chief, met with reporters shortly before moving over to the number two science and technology position at CIA. When Meyerriecks listed the community’s top three priorities, she placed “CT, counterterrorism, of course” in the second slot and omitted cyber programs.

CT is usually a bureaucratic euphemism for the drone war. It’s something you don’t hear a lot in briefings. Cyber, on the other hand, is a favorite topic.

I wasn’t the only one whose ears perked up. Minutes after the briefing, a spokesman for Meyerriecks sent reporters an email saying the top three priorities of the community are: “1) People 2) cyber 3) Preserving R&D.”

I wondered to myself whether the CT reference was an unwitting glimpse of the truth. It’s always seemed odd that counterterrorism wouldn’t rank among the top priorities, given the drone war and what we now know is an aggressive and expensive series of surveillance programs. I filed away the anecdote as something to explore later. It certainly didn’t warrant a story at that point.

When the Office of the Director of National Intelligence posted the transcript on its website, it replaced the CT reference with the phrase “cyber, of course.”

The polished transcript is still out there, just one click away from the transcript of Director James Clapper’s interview with MSNBC's Andrea Mitchell.

I asked about the change. A spokesman said Meyerriecks simply misspoke when paraphrasing the standard leadership line about priorities. I can accept that explanation. What I can’t accept is changing a transcript. By definition, a transcript means a person’s spoken words. It’s not what the public affairs shop or anyone else wishes had been said.

If Clapper’s office was worried about erroneously signaling a shift in priorities, fixing the transcript wasn’t the only way to handle that. It could have decided not to post the transcript or it could have included an editor’s note showing the error and correction. Changing history, even in small ways, is a slippery slope that the government should never set foot on, especially when it’s trying to win back trust.

Mike Birmingham, the spokesman who organized the briefing, stood by the change. He told me by email that Meyerriecks knew about the alteration and that I missed my chance to object:

“The ODNI Public Affairs Office changed one word in the Dawn Meyerriecks roundtable transcript to accurately reflect the ODNI leadership’s top three priorities after consulting with Ms. Meyerriecks and the reporters present, and no one objected, including Ben Ionnatta (sic.).”

I didn’t notice the reference to changing the transcript until I reread the post-briefing email. I certainly hope I would have objected, but I can’t see why it should have been up to me or anyone else to do so.

This issue has bothered me for weeks, so I emailed Bernadette Meehan, a spokeswoman for the White House national security staff. I asked Meehan about the administration’s policy on changing transcripts. She referred me back to Clapper’s office.

The Obama administration wants to be trusted. A good place to start would be to remember the government's responsibility to leave an accurate historical record.

A former spy on leaks, drones, humint

Some retired American intelligence officers are quietly appalled by the Snowden surveillance leaks. Spy novelist Michael R. Davidson is loudly appalled. Davidson retired from the CIA in 1995 after a 28-year career that included stints as a station chief focusing on the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. He's been leading a quiet life in rural Virginia, aside from the occasional speaking appearance to promote his books. He's disturbed by the moral comparisons he sees being drawn between the U.S. and countries like China and Russia in the wake of the surveillance revelations. I spoke by phone with Davidson and pushed him hard about his views. Isn't the U.S. drifting toward the practices of the governments he disdains? Wouldn't it be better to invest in spies than in storing billions of phone records in the cloud? Davidson still relishes a frank exchange of views.

Damage from the Snowden case >> “My concern is for what else he’s telling our adversaries, and it also has put us in a bad situation in the world. The Russians, the Chinese and others can use this to beat us over the head with this moral equivalency that they like to use to justify their own misdeeds.”

Possible boon for China >> “From the moment (Snowden) set foot on Chinese soil, he was under the control of Chinese intelligence. That’s just the way things work.”

The "trap of moral equivalency" >> “It’s easy for people to sit on a fence and cast aspersions in both directions, but there comes a point where you have to choose sides. Are we going to be on the side of the United States, which stands for democracy, freedom of speech, freedom of religion -- all the good things we know about America? Or are we going to stand on the side of the Chinese communist government, which represses its people?”

Surveillance >> “We cannot really defend ourselves with one arm tied behind our backs. The NSA is a very powerful instrument to protect the United States, so I will defend it for a long time.”

Values intact >> “I’ve never seen any indication that our intelligence agencies are involved in the repression of the American people. That would be anathema to my thinking and I think to the thinking of people in the intelligence community.”

Baffling security lapse >> “I don’t know how it could be possible that within the intelligence community in a sensitive position, you would allow someone to have a computer with a thumb drive. I really don’t understand it. When I was in the CIA way back in the dark ages, all of our computers’ floppy disk drives were disabled....”

Private spies >> “Really I worry a lot more about Google than I do about NSA to tell you the truth.”

Telephone metadata >> “If you want to find metadata on your own, just open a phone book. It’s, the phone company that owns your telephone numbers, and owns the information about what other numbers you’ve called…”

Human intelligence >> “I’m a big fan of humint, of course, because that’s the world that I was involved in. But I certainly don’t negate the importance of sigint or masint or any of the other ints that we work with… you can detect patterns, you can detect connections via sigint that will lead you to a great humint recruitment, for instance.”

Dwarfed by NSA >> “The NSA’s budget dwarfs the CIA’s budget and always has simply because of what you’ve just stated -- that’s the cost of the technology.”

Infiltration ain’t easy >> “Today, recruiting assets in terrorists organizations, I think, is well nigh impossible. It’s certainly extremely difficult.”

Historical double standard >> “You have a lament out there among legislators, in the executive branch and the public that, ‘Well, the CIA’s just not recruiting enough sources inside terrorist organizations.’ Both of those activities are activities for which the CIA has been excoriated in the past.”

Davidson elaborated by email: "One of the results of the congressional investigations into CIA activities in the 60′s was to prohibit the Agency from carrying out assassinations. More recently the Agency was severely criticized for recruiting agents with less than pristine pasts. The irony is that today, the Agency is directed to conduct relatively massive assassinations via drone strikes and criticized for not recruiting members of terrorist organizations."

Weakened tradecraft>> “We’ve had since 9/11 an emphasis on paramilitary operations for the CIA...These young folks, their first assignment is to pack on a nine-millimeter pistol and take off for the hinterlands of Afghanistan or Iraq, someplace like that...You have a situation where the CIA is tasked with the drone operation...So, we have an entire generation that basically has to be retrained and might find being a traditional spook a little bit boring compared to the adventure of carrying a weapon every place you go and meeting very dangerous people in very dangerous places."

Rebuilding humint >> “...the tradecraft practices that I learned and used throughout my career have atrophied at CIA…We have several years of rebuilding ahead of us in terms of our humint capabilities.”

Details emerge in classified Benghazi hearing

The commander of Africa Command at the time of the Benghazi attack said in a classified hearing that the White House did not consult him about security in Africa during the run-up to the Sept. 11 anniversary in 2012, according to a statement released by a House subcommittee.

The White House said it's not surprising that then-Army Gen. Carter Ham and his staff were not included in the anniversary preparations led by John Brennan, the president's counterterrorism adviser at the time. "Mr. Brennan ran a process that included the Office of the Secretary of Defense and Joint Chiefs, as well as the other relevant representatives of the interagency, ahead of September 11. It’s typical that COCOMs would not participate directly in those meetings, since they’re represented by JCS," said spokeswoman Caitlin Hayden by email.

Also during the June 26 hearing, the lieutenant colonel in charge of security at the embassy in Tripoli reportedly said he and a special forces team could not have gotten to Benghazi in time to make a difference. Lt. Col. S.E. Gibson said he was directed to stay in Tripoli to defend against a possible attack there, according to the subcommittee.

TEXT >>

Readout of House Armed Services Committee, Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations Classified Briefing on Benghazi

WASHINGTON--Today, the House Armed Services Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations received testimony in a classified briefing from three key figures involved in the response to the attack on Americans in Benghazi. General Carter Ham (ret), former Commander, AFRICOM; Lieutenant Colonel S.E. Gibson, former commander of the site security team at the U.S. Embassy in Tripoli; and Rear Admiral Brian Losey, former commander, Special Operations Command Africa, all offered accounts of U.S. force posture and planning ahead of the attack, and actions taken during and after the attack. While the subcommittee will continue to carry out appropriate oversight, today’s witnesses did clarify several matters with respect to the events of September 11 and 12, 2012.

Pre-9/11 Force Posture and Planning: On September 10, 2012 the White House issued a readout of a presidential briefing on 9/11 planning. The readout said the briefing was the culmination of “numerous meetings to review security measures in place” chaired by John Brennan. The readout also reported that the briefing included “steps taken to protect U.S. persons and facilities abroad, as well as force protection.”

When questioned about this process today, General Ham, the combatant commander responsible for one of the most volatile threat environments in the world, stated that neither he or anyone working for him was consulted as part of the Brennan 9/11 planning process.

Response to the Benghazi Attack: In his testimony, LTC Gibson clarified his responsibilities and actions during the attack. Contrary to news reports, Gibson was not ordered to “stand down” by higher command authorities in response to his understandable desire to lead a group of three other Special Forces soldiers to Benghazi. Rather, he was ordered to remain in Tripoli to defend Americans there in anticipation of possible additional attacks, and to assist the survivors as they returned from Benghazi. Gibson acknowledged that had he deployed to Benghazi he would have left Americans in Tripoli undefended. He also stated that in hindsight, he would not have been able to get to Benghazi in time to make a difference, and as it turned out his medic was needed to provide urgent assistance to survivors once they arrived in Tripoli.

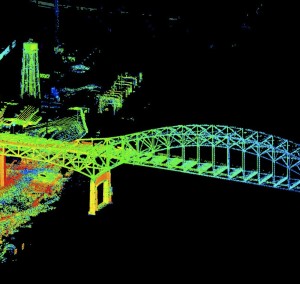

Budget clouds 3-D mapping of entire U.S.

Even in flusher times, the idea of hiring Cessna crews to bounce laser light off every square meter of the United States over the course of eight years sounded like a hard sell.

Lidar, or light detection and ranging, has been used in the U.S. for about 15 years as an urban modeling and terrain mapping tool. Lidar visualizations can help determine the best place to position surveillance cameras or snipers in a homeland security crisis. They can help FEMA predict flooding before hurricanes. On the highways, terrain data could even make cruise control more fuel efficient by giving advance notice of uphills and downhills.

Two years ago, when U.S. officials began laying the ground work to take that smattering of lidar data nationwide, they were probably braced for the standard questions about health (the light is safe, they say) and privacy:

“You can see the shape of my swimming pool; the slope of my roof,” said one fan of the technology. “Sooner or later, someone’s going to say, ‘I don’t know how I feel about that.’”

This year, the task has fallen to the U.S. Geological Survey to push the proposed 3-D Elevation Program forward in Congress against even bigger forces: sequestration cuts and the further reductions lawmakers are eyeing for the USGS parent agency, the Interior Department. That's quite a climate to start a major new initiative.

“Some people would say it’s impossible – but I would say ‘not easy’ is a better characterization,” said Larry Sugarbaker, senior adviser for USGS’s National Geospatial Program, which would include 3DEP.

Here's USGS's argument: Although sequestration doesn’t allow new starts, 3DEP isn’t exactly one of those. Lots of lidar data is already collected on behalf of individual states, NOAA, FEMA, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency and the Department of Homeland Security. The data is a hodgepodge, covering only about 30 percent of the country. It’s accumulated as the state and federal agencies tackle their unique missions: NOAA does coastal surveying; DHS and NGA map urban areas in three dimensions. No one does very much elsewhere.

The White House wants USGS to organize and expand collections into a country-wide National Lidar Dataset that would be refreshed every eight years. All told, USGS and the other agencies would need to spend about a billion dollars -- $146 million annually – to get it done. Today, the U.S. spends about $50 million a year on lidar.

Some call the new approach multi-agency funding. Others call it passing the hat. Either way, “We count on NGA and others to contribute” and “to increase their collections,” Sugarbaker said.

The 3DEP cost estimate comes from a March 2012 study called the “National Enhanced Elevation Assessment." It was drafted by the engineering company Dewberry under contract to USGS. Dewberry estimates that mapping all of the U.S. in 3D would generate “benefits” valued at anywhere from $1.2 billion to $13 billion a year. The study doesn’t explain the huge range. Most advocates have seized on the higher figure. It includes estimated decreases in property losses and a 25 percent reduction in the costs of collections through higher volume.

Sugarbaker conceded that Dewberry, which performs surveying and mapping work, would be a beneficiary of 3DEP, but he said working with the company made sense because of its expertise. The conflict of interest was dealt with by giving Dewberry very specific marching orders to provide information – not judgments – about a range of alternatives.

USGS decided on the second best lidar data, called “Quality Level 2.” Two pulses of laser light will bounce off each square meter of the surface, instead of eight times under Level 1.

For its part, USGS wants $23.7 million in 2014, an $11 million increase. Most of the increase would be spent on data acquisition by the private sector. Two additional federal positions would be added to bring the team to 59.

According to a draft USGS implementation plan, a solicitation would be released in June 2014 followed by the first contract awards in November to those who would fly the planes and process the raw data. Those will be called Geospatial Products and Services contracts.

The 3DEP proposal has lots of industry backers, not surprisingly. The initiative would be a welcome “strategic approach,” said John Pallatiello, executive director of MAPPS, the Management Association for Private Photogrammetric Surveyors in Reston, Va.

The U.S. has been collecting lidar over about 2 to 3 percent of the country a year, according to the Dewberry report, meaning it would take 35 years to map the whole country.

Sugerbaker said the rate has climbed to about 5 percent more recently, but that the basic point still holds. It will take a government initiative to map the whole country and keep the data fresh.

“We do the best job we can to stitch it together. The result of that is about a third of the country is done. But that data is aging. North Carolina is about 11 or 12 years old,” he said.